Due to the holiday break, I had nine days all to myself, and I decided to go on a Scandinavian tour. Peaceful and quiet... I didn’t want to hear the sound of car horns, only the sound of bicycles. On the last day of March 2025, I was in Stockholm. The weather was as beautiful as it can be. Honestly, it wouldn’t have mattered to me. I had made plans to meet a friend who takes photos of Stockholm, and we agreed to meet in the most well-known spot in the city center.

“Where would you like to go?” she asked. I opened my Google Maps and looked through the cafes I had saved. I picked one. “Let’s go here,” I said. She nodded and replied, “That’s a lovely spot.” We got off the metro and started walking down a street. I suddenly realized it was the same street I had walked earlier that morning. We passed through a small park and were getting close to the café when something on the left caught my eye—a photo gallery. Through the window, I saw two or three people and a wall filled with black and white photographs. I couldn’t resist. “Let’s go in,” I said.

I always visit the photo galleries that pop up on the street with great enthusiasm. Especially the art galleries in the Marais district of Paris never fail to excite me….

The gallery name is GALLERI FOTOGRAFI. It was quiet and humble. Three walls were covered with black-and-white photographs. On a small coffee table, there were some flowers, sugar cubes, half-eaten biscuits, and mugs that had just been emptied. I started looking closely at the photos and recognized the rooftops of Gamla Stan.

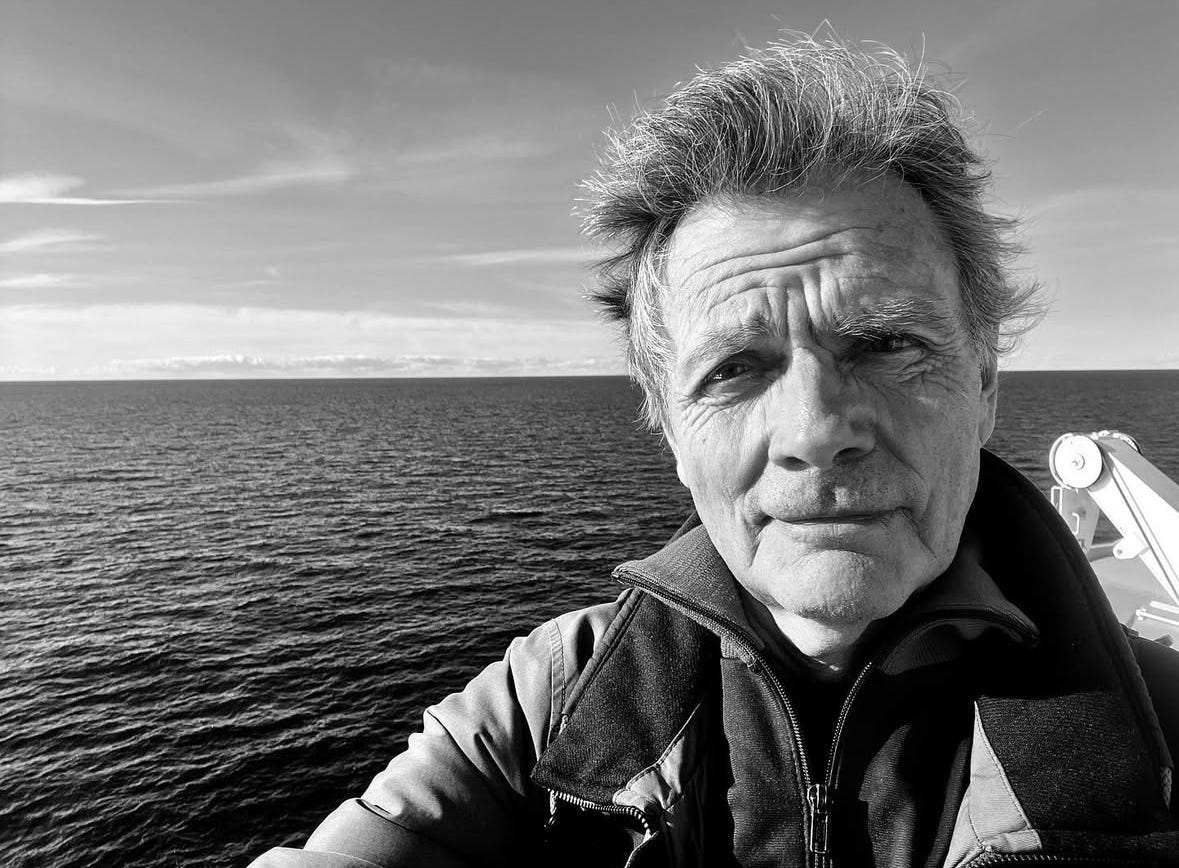

That’s when we met the photographer—Bernt Lindgren. I told him I was curious about the exhibition. He pointed to one of the photos and said, “I took this when I was twelve, with a camera my father gave me.” The photo showed his younger brother, who had just fallen off a bike—his face still marked with a fresh scrape.

He explained that many of the photos on that wall were taken in Fårö, on the island of Gotland, when he was a child. Rural life, captured through a twelve-year-old’s eyes. Then he turned to the opposite wall—photos of Stockholm in the 1970s, mostly around the city center and Gamla Stan. He said he wanted to create a contrast between the simplicity of the countryside and the growing rhythm of the city. The exhibition was called “Bernt Edvard 12 år.”

He told us about his life working as a driver at train stations, and how he had always wanted to be an architect. Photography was only something he could pursue in his spare time. Now 76 years old, Bernt had shared with us the images from his 12-year-old self. And what a gift that was. The conversation grew warmer. I shared that I was a visitor from Istanbul, with a background in photography and a lifelong passion for it.

Hearing I was from Türkiye, Bernt reached for a book from one of the shelves and placed it in front of us. It was about the Turkish photographer Lütfi Özkök. To my surprise, I had never heard of him before. What a lovely coincidence—to discover him for the first time in a quiet gallery in Stockholm.

Flipping through the book, I learned that Özkök had moved to Sweden after marrying a Swedish woman. His work focused entirely on portrait photography. And then, there it was—the name and the face: Nâzım Hikmet Ran…

One of Turkey’s greatest poets, who had lived much of his life in exile. I discovered that Lütfi Özkök had photographed Nâzım Hikmet in Stockholm in 1959. A deep sense of nostalgia filled me. Meeting Nâzım Hikmet in Stockholm—through the lens of a fellow Turkish artist, living far from home.

Özkök had taken what would become one of the most iconic portraits of Nâzım Hikmet. Right here, in Stockholm.

Nâzim Hikmet (1902 –1963)

On Living

III

This earth will grow cold,

a star among stars

and one of the smallest,

a gilded mote on blue velvet—

I mean this, our great earth.

This earth will grow cold one day,

not like a block of ice

or a dead cloud even

but like an empty walnut it will roll along

in pitch-black space . . .

You must grieve for this right now

—you have to feel this sorrow now—

for the world must be loved this much

if you’re going to say “I lived”. . .

Tack så mycket Bernt!

Eda Eriş